Our Man, the American journalist George Packer’s new 600-page biography of Richard Holbrooke, is a masterful book, not just for what it says about the late US diplomat himself, but also for how it portrays the evolution of US diplomacy more broadly.

Of Holbrooke, Packer tells us that he “devoted three years of his life to a small war in an obscure place with no consequences in the long run beyond itself.” Here, I must confess some bias. While working to bring an end to that dreadful war in Bosnia (Packer’s “obscure place”) in the 1990s, I came to know Holbrooke fairly well. And, after that, we bumped into each other periodically, particularly in the context of the war in Afghanistan, which has lingered on nearly a decade after Holbrooke’s passing.

Holbrooke’s life in public service began in the rice fields of Vietnam’s Mekong Delta in the early 1960s, when the United States got itself into a war it obviously didn’t understand. As a young, extremely ambitious foreign-service officer working in rural development, Holbrooke could see that the realities on the ground were far messier than decision-makers in Washington, DC, were willing to acknowledge.

Needless to say, Holbrooke’s instincts were correct. The seasoned hands in Washington pursued further escalation, believing that indiscriminate bombing and a rising enemy death toll would do the trick. Little effort was made to establish a credible state that could sustain itself after the war had ended. And, soon enough, younger generations of Americans had taken to the streets to protest what looked like a pointless war. US President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, would go on to abandon the disastrous affair after a “decent interval,” allowing them to focus on the great game of managing China and the Soviet Union.

The lesson of the Vietnam War stuck, at least for a time. Though US President Ronald Reagan ordered the invasion of Grenada in 1983, there was no need for an extended occupation of that country. And following the bombing of US Marine barracks in Beirut, Reagan was quick to retreat from Lebanon. The consensus was that there should be no more quagmires. America should keep its feet dry and focus on great-power issues.

But after the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the world seemed to become more complicated. The international community could not ignore the chaos in Somalia and the genocide in Rwanda. And then there was Bosnia, with its “ancient quarrels.” Everyone hoped that the problem would just go away; but, of course, it didn’t.

In the event, the US had to abandon its policy of detached neglect and wilful ignorance. The conflict in Bosnia demanded real diplomacy. It wasn’t resolved with bombs, but by diplomats who had ascended from the muck of the Mekong Delta to “the treetops” in Washington, DC. Holbrooke, along with US President Bill Clinton’s national security adviser, Anthony Lake, saw that difficult and painful compromises would be necessary. Diplomacy eventually led to peace; and Clinton, who was sometimes otherwise engaged, presumably welcomed the positive contribution to his presidential legacy.

To Packer, Holbrooke’s story is also a story about “the end of the American century.” As a historical matter, this feature of the book’s narrative is vastly exaggerated. But Holbrooke’s life and career undoubtedly did coincide with a period in which America’s ambitions occasionally exceeded its abilities. Still, even in areas where the US fell short of its goals, matters might have been much worse had it made no effort at all.

One can debate endlessly whether the US is any good at the things Holbrooke wanted it to be good at, such as counterinsurgency wars. Packer, for his part, concludes that it is not, “because we don’t have the knowledge and patience.” Too few Americans, he argues, are willing to “spend the years out there necessary to understand the nature of the conflict.” The US prefers that its wars be “quick and decisive,” because “we like firepower more than we want to admit.”

Until he collapsed at his post in 2010, Holbrooke tried to apply everything he had learned during his career to the conflict in Afghanistan. But, again, he ran into the same Washington roadblocks that had been there since Vietnam. “We Americans,” Packer writes, “have never been good at managing the internal business of other countries. We’re lousy imperialists. We are too chaotic and distracted – too democratic. We don’t have the knowledge, the staying power, the public support, the class of elites with the desire and ability to run an empire.”

And so, as Our Man illustrates, America just stumbles on. The war in Afghanistan continues, though the Trump administration seems to be waiting for a “decent interval” before abandoning the conflict.

And Bosnia is still a troubled place. The politicians representing its three nationalities are constantly quarrelling and trying to undercut one another. Many of its young people want to leave, to seek a better future in Germany or elsewhere. Still, while Bosnia has not become another Switzerland, it has peace. Over the past quarter-century, fewer people have been killed by inter-ethnic violence there than in the suburbs of Paris.

For that, we owe a great deal to American diplomacy, and particularly to Richard Holbrooke. The world is a better place as a result of his service, and Packer has now given us a worthy monument to his career and the historical epoch in which he pursued it. – Project Syndicate

* Carl Bildt is a former prime minister and foreign minister of Sweden.

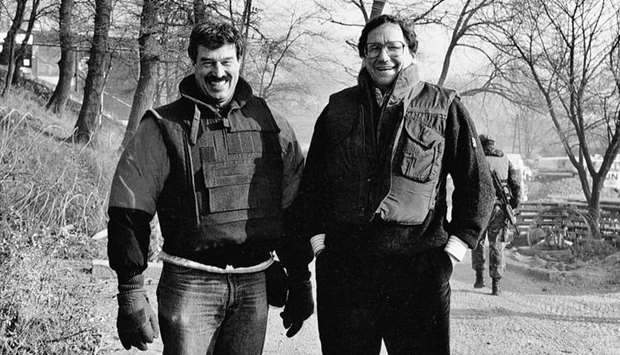

Richard Holbrooke (right) and Lionel Rosenblatt (left) on the road to Sarajevo. Credit: Courtesy of Sylvana Foa