Forget about a 40-year-old virgin — how about a 40-year-old med school student?

Lee Mark Nelson made the most dramatic leap of his life a decade ago, when he was at the top of his game, celebrated for essaying the shy assistant manager in She Loves Me at the Guthrie, the dutiful Father in Ragtime at Park Square and the big-hearted Daddy Warbucks in Annie at the Children’s Theatre.

He gave it up, standing ovations and all, to pursue something seemingly unrelated. The Juilliard-trained leading man quit his highly respected stage career to embark on a daunting path to become a physician.

“One of the things I respect most in people, generally, is courage,” said Michelle O’Neill, a celebrated actor and teacher who also is Nelson’s wife of 21 years. “It’s hard to have courage in this world — to say your true feelings, be honest with yourself and follow your passion. Mark has that.”

Nelson had the encouragement of family, mentors and the community. But it takes more than that to go back to school with kids who could be your kids, and take pre-med courses like organic chemistry, physics and biology. He also had passion and a strong work ethic.

“Mark is a man of enormous integrity, sensitivity and intelligence,” said Joe Dowling, the former artistic director of the Guthrie who directed Nelson in about a dozen shows. “That he has become a doctor is theatre’s loss but medicine’s gain.”

Nelson, whose brother, Kris Nelson, and sister-in-law, Tracey Maloney, also are highly regarded performers, sees it differently. The professions, he says, have a lot in common.

“Medicine has the perfect combination of so many of the things I loved about theatre,” he said. “You never stop learning, so every time you do a play, you’re learning a whole new world. At the micro level, it’s about heart and empathy and understanding what it is to be human. It’s not a hard jump to make.”

Imagining his future

There are many ingredients to Nelson’s leap of faith. First, as he was pursuing the acting life in the Twin Cities, a place the Utah native first worked in 1996, he looked around at the community and tried to imagine where he would be in a decade or two.

What he saw was both encouraging and discouraging. After a lifetime of honing their skills and building up their résumés, some veteran actors were still cobbling together a living from bits and pieces of theatre work and teaching. Such instability seemed untenable to Nelson, who desired to be an anchor for his two daughters, now 17 and 15.

“People in theatre say that if you can do anything else and be happy, then do that,” Nelson said.

So he began to explore other interests. He thought about starting a business, but found that he didn’t have that fire in his belly. He thought seriously about law, taking the LSATs and gaining admission into schools on the East Coast. But one day while in New York, he was walking in Manhattan when he saw a crowd gathered on a sidewalk at a famous law building. An attorney had plunged to his death, probably a suicide. He took that as an omen.

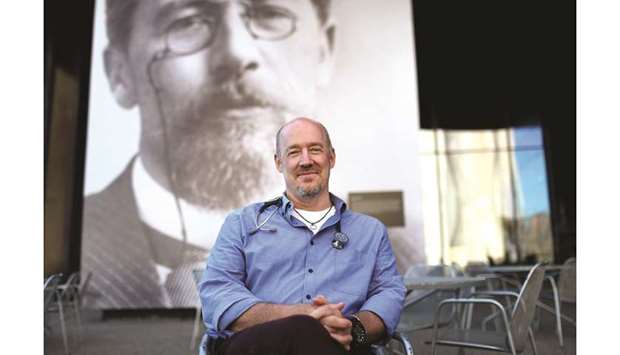

It was, coincidentally, about the same time that Dr Jon Hallberg, a physician and arts lover who teaches at the University of Minnesota, called over to the Guthrie to find someone to commission for a one-person show on Anton Chekhov. Best known as a playwright but also a physician, Chekhov is one of Nelson’s favourite playwrights.

“Everyone said, ‘Oh, that would be Mark Nelson,’ ” Hallberg recalled. The two men met, and Nelson quickly won the commission, performing the show onstage at Northrop auditorium.

Nelson later asked to meet Hallberg for coffee.

“Mark said that he had this crazy idea and wanted to run it by me,” said Hallberg, who became a fan and a champion of Nelson. He had seen him act in many shows, including Ragtime, Annie and The Master Butchers Singing Club, the adaptation of Louise Erdrich’s novel that premiered at the Guthrie.

Hallberg also knew that in HMS Pinafore, Nelson had understudied three big roles and got called on for each of them. He referenced that in his med school recommendation letter.

“If someone can have the play memorised, step in at the last moment and not miss a beat, then that person can remember every bone in the body,” Hallberg said. “Mark is an amazing combination of brilliance and kindness and compassion.”

Not to mention bedside manner. Theatre artists, who study the psychology of people and have to be emotionally present onstage, are well primed to be doctors.

“Who better than actors to understand empathy and the human condition,” said Hallberg, who comments frequently on public radio. “They spend their lives putting themselves in other people’s shoes. We try to teach med students this, but it’s a tough sell sometimes. Mark just gets it.”

Shy kid

It is said that acting is the shy person’s revenge, and that’s true of Nelson. The middle son of an engineer father and teacher mother, he grew up in Salt Lake City. He’s still very self-effacing, but has a way of making you feel like you’re the centre of the world. That same charisma connected him to audiences. And it’s the same thing that’s now connecting him to patients.

But he didn’t know that he had it at first. He found out at the University of Utah at 18 when he met Ken Washington, a legendary teacher and director who would later become the Guthrie’s director of company development (and who also taught at Juilliard, where his students included Nelson and O’Neill).

Nelson described Washington, who died in 2014 and is revered by legions of actors, in celestial terms.

“When you come across a light like Ken, you say, that’s a life worth living,” he said. “He was my mentor who helped me transition to life as an adult and to theatre.”

Now another mentor has helped him transition to medicine. Hallberg likens a doctor’s visit to a small set piece.

“The knock on the exam door before you go in is essentially curtains up,” Hallberg said. “The doctor has to connect as quickly as possible with a patient you may have never met. Sometimes medicine is like jazz, that way. You’ve got the notes and score, but you’ve got to riff and improvise.”

Nelson agrees.

“When I go into a patient’s room, I’m seeing someone with all kinds of anxieties and pains,” Nelson said. “I get a chance to meet someone and get to help them.”

Theatre, he said, has trained him in other ways that will be helpful for medicine. Nelson recalled a recent incident when he was walking with his family.

“I didn’t have the dog on the leash and this group of people was coming across the bridge,” he said. “By way of warning them about the dog, and telling them that it’s friendly, I started to say, ‘Hello, guys.’ But then this woman immediately cut me off, saying, ‘Don’t call me a guy, you fat, bald fart.’ My first thought was, ‘How did she know I was bald?’ I had a hat on. My second thought was ‘Obviously, she’s not well.’ I wasn’t upset with her. I wanted to help.”

After a three-year residency in north Minneapolis, Nelson recently began practising family medicine at the Mill City Clinic across the street from the Guthrie Theater. He is parking in the same lot where he used to park as an actor. He passes the same images of Tyrone Guthrie and Chekhov and Lorraine Hansberry etched on the side of the theatre. And he recently saw his first Guthrie actor patient — a performer from the cast of Guys and Dolls. And while he has fond memories of his former haunt, where he did many seasons in A Christmas Carol, he’s not sad.

In this new chapter, he’s not getting under the skin of his characters. He’s helping patients to heal. Besides, he also is inspiring theatre folks like Maura Clement, who graduated from the University of Minnesota/Guthrie Theater BFA program in 2011, and now is enrolled in the Pritzker School of Medicine at the University of Chicago.

“What Mark did is brave, remarkable and against all caution,” said Clement, who will be 32 when she graduates from med school next spring. “It says that it’s not too late in your life, that you didn’t choose the wrong career the first time, and that you can pursue your dreams at any age.”

Nor has he completely forgotten his previous life. Nelson turned to Chekhov’s The Seagull to explain his transition from theatre to medicine. The main character, Trigorin, has a monologue where he talks about what it’s like to be an artist, Nelson noted.

“For everything that happens to him, there’s a part of his brain that thinks, ‘Oh, this is something I can use later in my art,’?” he said. “That was my life as an actor, especially the moments when people are in crisis. A part of my brain was filing away notes on how they’re coping or trying not to cry.”

He paused.

“That part of my brain is still there, but I’m no longer doing that,” Nelson said. “Now, I’m trying to help them with their problems. I feel much more engaged in people’s lives.” — Star Tribune (Minneapolis)/TNS

IN HIS ZONE: Dr Lee Mark Nelson poses for a photo outside the Guthrie Theater and an image of Anton Checkov, famed Russian playwright and physician, where Nelson once acted.