Renée Zellweger is making her way through a bowl of potato chips in the lobby of Casa del Mar, the beachfront Santa Monica hotel she used as an office for a couple of years while she was developing a television series, Cinnamon Girl, about four young women coming of age in Los Angeles in the late ’60s. The show, which didn’t get picked up, was loosely based on Zellweger’s own move to LA from Austin in 1993.

“I left on December 4, 1993 and got here on the 6th,” Zellweger says. “I took my boombox and my dog and drove my red Honda CRX. I guess I didn’t own that much because everything I did own was in the back of my car. And that’s a small car!”

Zellweger laughs at the memory. She laughs a lot, almost always with an exuberance and generosity of spirit. “Beautiful” might be her favourite word and, over a long lunch at her old haunt (salmon is added to a kale salad with the proviso that it be “destroyed” to the point where if the chef thinks “he’s done too much, tell him to be brave and go more”), Zellweger uses the word to describe Sequoia National Park, ’66 Ford Mustangs, Janis Joplin, the feeling of quiet in the hills above Malibu where she now lives and the smell of freshly ground pepper.

She’s dressed casually — jeans, black Dr Martens boots, a faded long-sleeve shirt and a frayed Houston Astros baseball cap, which she describes, as she often does, as “not a hat but my hairdo.” She has just returned from Australia, where she was promoting her new film, Judy, a moving portrait of Judy Garland that takes place during a chaotic London concert residency a few months before she died in 1969.

“My brain hasn’t arrived yet,” Zellweger says, noting a jet lag that wouldn’t otherwise be apparent. “I’m expecting it any minute. The iced tea is a very helpful friend under the circumstances.”

Nicole Kidman, who became friends with Zellweger when Cameron Crowe cast the latter opposite Kidman’s then-husband Tom Cruise in 1996’s Jerry Maguire and then worked with her seven years later in Cold Mountain, says that kind of off-kilter self-deprecation is what makes Zellweger so wonderful.

“Renée has a great spirit and absolutely doesn’t conform,” Kidman says by phone from her Nashville home. “She’s got an untapped well of talent. We’ve seen some of it, but not anywhere near what she’s got inside.”

Zellweger’s turn as Garland in Judy reveals facets of her gifts — and of herself — that we’ve never seen before, playing a show business legend struggling with loneliness, self-doubt, crippling insomnia and, as much as anything, the emotional toll of simply having to be Judy Garland. The singer is drained and world-weary, but living by the adage that the show must go on.

Garland’s five-week London club engagement at Talk of the Town could be glorious or an absolute train wreck depending on the night. Audiences cheered and heckled, accordingly. The tabloids delivered scathing reviews. Judy, Zellweger suggests, offers a different perspective from what has often been written of this time in Garland’s life.

“She deserved better than that,” Zellweger says. “The movie leaves room for empathy and a deepening admiration. It’s not easy to do what she was doing, even in the best of times.” She pauses. “It’s a funny job, trying to conjure something like that.”

Zellweger, 50, has always possessed a sense of perspective about being an actress. When she came to Los Angeles, she settled in a pre-gentrified Hollywood, looking for an “interesting place for a young person to come and have a great life adventure.” She was seeking remnants of Charles Bukowski’s Hollywood (“I didn’t want to land at Universal CityWalk”), and found them while working at a dive bar and living in a neighbourhood where drug deals were routine. She eventually decided that she’d stop replacing the car window on her Honda CRX because … what’s the point?

“Every bit of it seemed so exciting and hilarious to me because it was all so unlikely,” says Zellweger, who graduated from the University of Texas with a degree in English, having taken just one drama class.

“You know, I just thought it’d be fun to try,” she continues. “And suddenly there was an agent calling. I still have no idea how he got the number. Then I had a meeting at Paramount with a really nice casting director. And they were going to let me on the studio lot! I got the parking pass and I’m following the map to her office and that was just so funny. They let me on the lot! I didn’t have any credentials. I was just faking it!”

She landed Jerry Maguire a couple of years later and spent the early part of the new century at the Oscars, earning nominations three consecutive years for Bridget Jones’s Diary, Chicago and Cold Mountain, winning for the last film.

That time period feels like a blur to her and she seems to prefer her 40s, a decade in which she focused more on her life than her career. (“She’s very private and always had her priorities outside of work,” Kidman says.)

“There was a cocktail waitress I worked with in my 20s and we were chatting about something and I was asking, ‘So, you’re 20 … ’ and she said, ‘Oh no, honey. I lost my 20s a long time ago.’ And I thought, ‘I never want to think about life that way. Never. I want to feel like it’s a triumph having gotten to use them all.’ And that’s how I feel about my 40s. Triumphant. I used them.”

Indeed, there’s a delightful go-with-the-flow quality to Zellweger, who will happily regale you with nostalgic stories set in the days before smartphones where “you’re in the middle of a national park and you’re not sure you’re going to get to the other side before you run out of gas and there’s no way to contact anybody because there’s no trucker who’s going to hear your CB radio.” She cops to spending a night or two in gas station parking lots, waiting for them to open.

“Getting lost, trying to figure out how to get by on your wits … I wouldn’t trade that for anything,” Zellweger says, tugging on her sleeves.

Making Judy, she says, was a daily battle of figuring things out and just plain denial about what she was trying to do. There were times when she felt disheartened. Zellweger has a strong voice — she was going to star in a Joplin biopic many years ago before a Writers Guild strike scuttled it — but singing Garland’s showstoppers was a two-steps-forward, one-step-back challenge.

The movie ends with Garland singing Over the Rainbow in front of a sold-out theatre. Filming that performance, Zellweger says, made her think of the ways that indelible song takes listeners to a place in their lives when they first saw The Wizard of Oz. Or maybe last saw The Wizard of Oz. And she thought of what the song meant to Garland and that she was still singing it during that late, desperate period of her life.

“Knowing what she’s going through … and she’s still singing about hope,” Zellweger says. “That makes me smile.” — Los Angeles Times/TNS

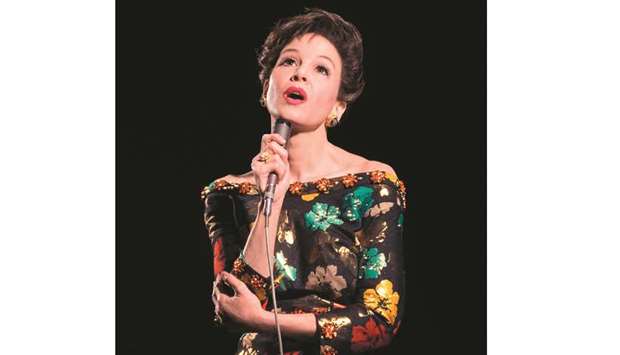

SHOWSTOPPER: Renu00e9e Zellweger as Judy in the biopic Judy.