I went away as a kid into the service and came back an old man. I had experienced life in a different way. I saw death firsthand and lived off the land. I knew what it was like to be hungry and mostly to fear the unknown.

From day to day, you didn’t know if you were going to make it. The first thing that gets into your mind when you see a dead guy is: This could have been me.

I was inducted into the Army on October 16, 1941, when I was 21. My basic training was at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, and then I was assigned to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to the 9th Infantry Division. I was primarily a rifleman, but my speciality was in high explosives. My job was to find mines. I was at Fort Bragg when the Pearl Harbor attack happened.

Most of the soldiers in my outfit, the 15th Engineer Combat Battalion, were from New England. They were really nice guys, working stiffs like I was, punched a clock.

When my squad looked for mines, we’d have four guys with mine detectors and we’d be about 10 feet apart. We would scan the ground, and when we found a mine, we would mark it with a rod and a flag that said MINE. We’d open up a lane. Then the rest of our outfit would come in and they’d disarm the mines or detonate them. They had the really tough part.

The first casualty in our outfit was a medic. He was on his way to a latrine and a sniper picked him off. That happened in Africa.

In Europe, a good friend of mine from Scranton stepped on an antipersonnel mine and it blew him in half. I was in the area when it happened. I heard the explosion, but we heard a lot of explosions and you never knew it was going to be one of us. We covered him with a GI blanket.

Especially in Europe, we blew up pillboxes. You couldn’t destroy them, you’d have to have an atomic bomb for that, but we could disable them. We’d destroy the insides.

There was a pillbox that my squad had to disable. Four of us had wooden boxes of TNT, 40 pounds of it. The pillbox was inactive. If there were Germans in there, they weren’t firing, or they were hiding somewhere else. We had to prepare the fuse, and we had to know how much time we’d have after we set it.

We timed the fuse for four minutes and lit it. I was the last guy out. We got a good ways from there, and we were looking at our watches. Five, 10 minutes and it didn’t go off. I turned to my foxhole buddy and said, “You know what this means.” “Yeah, you’ve got to go down there and see what happened.” I said, “I can’t ask anybody to go, but I want you to come with me.” So we went down there.

What happened was, I was panicking after we lit the fuse — I had to get out of there and I slammed the door shut and the fuse was under the door. It burned to the door and stopped. It was a heavy steel door, flush with the floor. I should have closed it partly. We relit the fuse and got away from there, and this time the pillbox blew.

The danger in horseplay

The war in Africa was a different kind of war that we weren’t trained to do. In Europe, you knew where the enemy was. In the desert, you had to look for them. We went on patrol at nighttime to make contact.

At the Kasserine Pass (in Tunisia), we were supporting services on the periphery. We got some of the shelling, but we weren’t in combat. We were behind the guys in the front lines, and when they retreated, we just packed up and followed them.

After the African campaign, we invaded Sicily. Most of our combat was in the area of Mount Etna, the volcano. It was woods like the Poconos. The Germans were retreating, and the natives took good care of us. They made spaghetti. We paid them with cigarettes, instant coffee, tea bags. We gave the kids chocolate candy. We dealt with mines, but they weren’t as extensive as they were in Africa and later on in Europe.

One day we were on R&R, rest and recuperation. Three of us were swimming in our skivvies in the Mediterranean, horsing around. We didn’t know it, but we were drifting out, caught in the undertow. How were we going to make it back? One guy lost it completely. I had to turn him around to hold him, because if I faced him, he’d grab ahold of me and we’d both go down. I could hold him with one arm, because he wasn’t struggling, he was so out of it.

My other buddy, Billy Davidson, was giving up, willing to die. He said to me, “Save yourself.” He was within my reach, so with my other hand, I held onto him by the back of his skivvies. I said, “Don’t fight the ocean. Just keep your head up, save your strength.”

I knew what I was doing. When I was a kid, I was a good swimmer. I was a junior lifeguard and I was on the swim team at Jordan Park. But I couldn’t have lasted forever.

A fisherman came by and saw that we were in trouble. He had a big wooden boat, and he hauled us in one at a time. He saved all our lives. When he brought us to shore, he took off. They laid us out on the beach and we couldn’t move. We were exhausted.

We went on to England to prepare for the invasion of Europe. On June 10, 1944, D-Day plus four, we crossed the English Channel on an LCT, a landing craft tank, and landed in Normandy at Utah Beach.

The LCT didn’t bring us all the way in to shore. When it stopped, we walked down the ramp into water up to our waists. We held our rifles up. The noise was deafening. There were shells popping all over, dead bodies scattered around. The beach was so crowded with men and material, it was impossible to find each other. You didn’t know who was beside you, only that he was a soldier, too. I didn’t see anyone else in my outfit for 10 days. It was chaos.

I was on the beach and inland a little bit for five days. Then our commanders started pushing us off the beachhead because we had to make way for stuff coming in. We encountered paratroopers hanging in trees –– dead. The Germans had killed them in the trees.

Gnawing hunger, bitter cold

When you’re hungry, that’s an itch you can’t scratch. In France, we were held up at the hedgerows. Kitchen couldn’t get to us. My buddy pulled onions for dinner. Raw onions burn all the way down. A day later, you drink water and it burns all the way down.

In the Huertgen Forest (on the border between Belgium and Germany), there was a lot of frostbite. People had frozen feet, and we didn’t eat. Where would we go to eat? Our kitchen couldn’t get up there to feed us.

I was fortunate. I didn’t get frostbite, and neither did my foxhole buddy Joe Dempsey — he was a detective from Brooklyn.

During the Battle of the Bulge, it was 8 degrees and we couldn’t dig a foxhole. The Germans had artillery that was considered an air burst. It would hit the tops of the trees. The trees were sometimes sheared in half, and a lot of them were turned over. Joe and I would crawl under these fallen trees in the snow and hug each other to keep warm. Sometimes I wonder how I ever got through that, not only me but all of us there.

One of the most horrendous noises I experienced was lying on my belly with shrapnel flying overhead, sucking air. That was horrible, frightful.

At Elsenborn (in Belgium) we came to a forced-labour camp. There were French, Italians and other nationals in there. They would do farmers’ work in the fields. An old guy, a German civilian, ran the place. We didn’t know it was a camp until we got to the gate. Some of the prisoners came running up to us. They were the walking dead, skinny as hell. We couldn’t do anything for them. That was for our rear echelon.

After the Germans were driven off the Rhine at Remagen, they zeroed in on the bridge and fired 88 millimetre shells every 10 minutes. It was harassing fire. When the shelling stopped, you looked at your watch and said, I’ve got 10 minutes to get the hell out of here. We ran across, and when we got to the other side, they started shelling again. The Germans had rigged the bridge with explosives, but it never blew up. A few days later, the bridge collapsed.

When we were held up in a town in Germany, we usually stayed in a house. A couple of us guys were in this one house, and a woman lived there. She was a teacher and spoke English well. We got to talking to her, and she couldn’t believe that we didn’t rape or kill her. The German people had been warned about Americans. She made us some scrambled eggs in a big frying pan and said, “I’ve got to tell you something.” She had a young daughter. We said, “Where is she?”

There was a mat on the kitchen floor, and she pulled it away and there was a trap door. The kid, 12 years old or so, was hiding under the trap door. We gave her cake and candy.

When we came to the Elbe River, there was hardly any fighting, only snipers. We weren’t aware that we shouldn’t be going any farther. The Russians weren’t supposed to go any farther than the Elbe on their side. We got over on the wrong side and our officers stopped us when they got orders from headquarters. We had to turn around and go back.

The war was over. I got through it all without a scratch — me and my buddy from Brooklyn. We were just plain lucky.

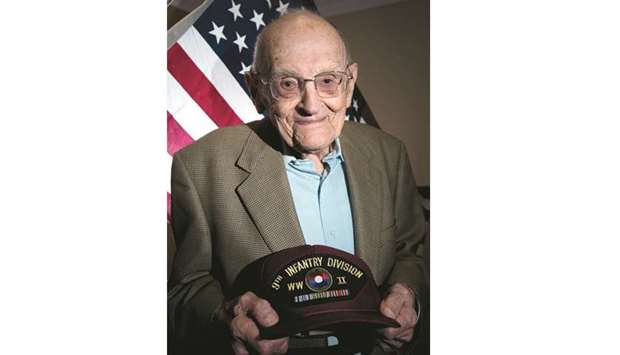

His 100th birthday is in February. —The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania)/TNS

UNDEFEATED: Good health permitting, Albert Fraind will be 100 next February.