Several alumni of the Education City of Qatar Foundation (QF) are at the frontline fighting against the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) in various hospitals in the US. In early March, Diala Steitieh was working her regular night shift at the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in Manhattan when she received a patient in his 30s with severe breathing difficulty and dry coughing.

The man did not have any pre-existing medical conditions, but had recently returned from a trip to Europe. Steitieh and her colleagues soon realised that the hospital had received its first Covid-19 patient and sprang into action, despite the fact there was no existing protocol for treatment of the new disease.

“Everyone was very cautious. We had at least three physicians, fully gowned and protected to transfer him, with double gloves, a N95 mask, and an additional mask over that for protection of the eyes,” recalls Steitieh, resident physician at the hospital and a graduate of Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar (WCM-Q), one of QF’s international partner universities.

Shortly after the first patient, Steitieh found herself in the middle of a global pandemic that would soon transfer New York City into one of the epicentres of the coronavirus outbreak.

“Over the course of two weeks, we went from having one patient in one night to having multiple patients overnight. So it was a very stark and sudden increase in the number of cases,” Steitieh noted.

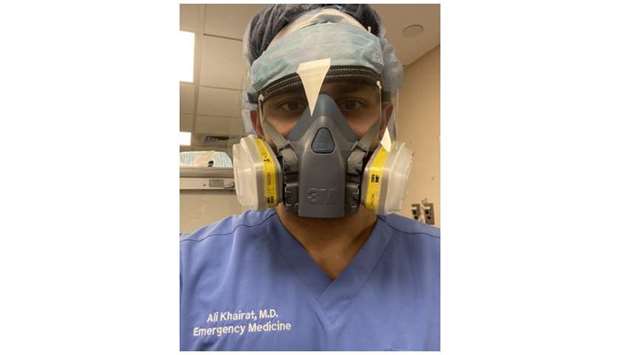

A few miles north of NewYork-Presbyterian, another WCM-Q graduate witnessed a similar progression of the crisis. Ali Khairat, a third-year Emergency Medicine Resident at the NYC Health + Hospitals/Lincoln saw his hospital transformed as the coronavirus outbreak unfolded in the city.

The rooms for non-urgent patients were converted into coronavirus-only wards, isolation rooms were activated, and the centre witnessed a huge influx of patients with respiratory problems.

“We have patients coming in with respiratory complaints, asthma, shortness of breath, and fever,” said Khairat. “We move them to the isolation room, protect ourselves with protective gear, and start interviewing the patient.”

Since the start of the crisis, the situation in hospitals across the US has become direr. Due to a shortage of personal protective equipment, healthcare professionals no longer have the luxury of following the standard procedure of changing masks and gowns for every new patient.

“We show up every day for work and can only pray that, this time around, the protective equipment will work,” said Siyab Panhwar, a WCM-Q alumnus who works as a cardiology fellow at Tulane Medical Centre in Louisiana, another US state seriously affected by the pandemic. “We are humans too, and we can also die. The lack of personal protective equipment is not ideal, but we just hope for the best when dealing with patients.”

According to Khairat, doctors are changing their ways of working to reduce the number of interactions with the Covid-19 patients.

Unfortunately, despite various safety measures, Khairat was infected with the virus and tested positive for Covid-19 in mid-March.

“I started developing mild symptoms and was asked to go home. It took five days for my test results to come back, but by that time thankfully I was already feeling better.”

Khairat is currently recovering under self-quarantine at home, but anxiously waiting to be able to get back to work. “If a physician is exposed and starts showing symptoms, and has to be pulled out of the hospital, that’s a huge strain on the system,” he said.

“We are understaffed and have a limited number of residents. And losing one senior resident in the team can be incapacitating to the department.”

Since the coronavirus outbreak struck, Khairat, Panhwar, and Steitieh have all worked extra hours and given up their days off to meet the demands placed on frontline healthcare workers.

Another key challenge for healthcare workers dealing with Covid-19 is that it is a novel virus with no set instructions regarding treatment or exactly how it affects the patient’s body.

“There is no protocol, and whatever we know changes every day,” said Panhwar. “In fact, it changes every hour. There is so much new information that’s coming in. This is something no one could have prepared for.

Khairat, Panhwar, and Steitieh said their commitment to continue fighting the virus outweighs any personal concerns, adding that their medical education and residency experience have equipped them to be on the frontline. “Being given all these tools through college and medical residency, and to actually apply them during a time when the world really needs you, is humbling and rewarding,” said Khairat. “It makes you feel you are participating in a human cause.

“I do have the confidence from the training I got in medical school and my residency, and that makes part of it easier, but it’s also just a very humbling experience to know that there are things that are quite unexpected and unplanned for,” added Steitieh.

According to Panhwar, the public can help the situation by staying at home and reducing the number of cases — what is referred to as ‘flattening the curve.’ “The best cure is to not get it,” said Panhwar, who has now started documenting his experience on social media channels to highlight the importance of social isolation and other protective measures.

“I can’t stress enough the importance of social isolation,” said Khairat. “It’s not just about protecting yourself, it’s about minimising the transmission to people who are at most risk.

“Previous generations were called to fight wars. We are simply called to stay on our couches.”

Steitieh, who echoes the importance of following advice from healthcare and government leaders, said what helps her during these difficult times is the fact that people have been messaging her — both from within the US as well as from Qatar, where Steitieh and her family reside.

Ali Khairat in protective gear.