Arsene Wenger still believes he could milk a cow but, as he says with a smile: “I haven’t tried for a long time. I might have lost the technique a little bit.”

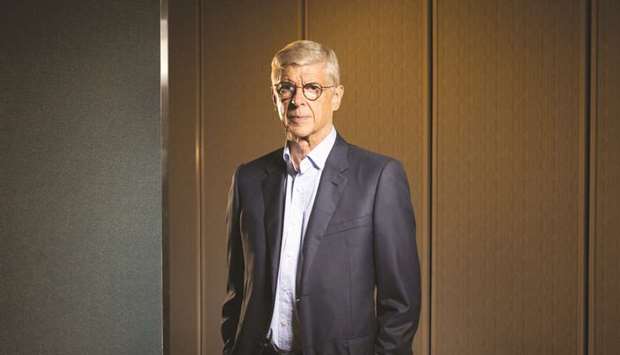

Wenger is one of the most humane and original thinkers in football and so it is not surprising that, moving beyond his “obsession”, we should spend 100 minutes talking about much more than the game that consumes him.

Whether describing how he learned to milk cows as a boy in the Alsace village of Duttlenheim in France, or reliving his first memory as a five-year-old watching his local football team while clutching a prayer book, Wenger stresses his life has been built on the pillars of hard work and faith. “It’s amazing that you make your life with the values from childhood. I think all the champions I have met have been the same. They had the root of their motivations in childhood.”

Having recently lost both his sister and brother in the space of six months, Wenger admits that writing his absorbing autobiography became more sombre. “Maybe because you feel guilty as well,” he says at his home outside London.

Wenger, who managed Arsenal for 22 years, shrugs ruefully. “When you have a passion you are selfish because the people who suffer the most are those around you. Unconsciously you always give an excuse because you think: ‘I will see them in one month.’ When you move out [of football], you think it’s a bit frightening how selfish and one-directional you were.”

Twenty-four years ago, in October 1996, Wenger’s immersion in Arsenal began as he became the club’s unknown new manager. He was only the fourth foreign manager to have worked in the English top flight – and the first three had been unsuccessful. Of course Wenger, who went on to win three Premier League titles and seven FA Cups, had a seismic influence on English football. But it is often forgotten how he suffered soon after his arrival.

He writes that “the pure hostility, lies, vile allegations … started with a radio host, a Spurs supporter, so I have been told. I had apparently been spotted in disreputable locations, in preposterous situations.”

The baseless rumours intensified. Wenger was living alone in a London hotel as Annie, his future wife, had yet to join him. He recalls that, over breakfast, people looked at him suspiciously or turned away. “It was intolerable. I wondered whether the world had gone mad, how such lies could be written without any evidence or truth, just to smear a man. I was very angry.”

Wenger sounds sanguine now. “I was quite surprised by the violence of these allegations because I didn’t know where they came from and why. But then I thought: ‘Why am I doing this job? Let’s focus on that.’ I was 47 years old and I knew who I was and what I wanted in life so it didn’t depress me too much. I had been in Monaco for seven years and in Japan two years before I arrived here. I knew that, in different countries, you sometimes face adversity.”

Did it shake his affection for England? “No. I love England, because it’s a country of passion, emotion, of sport and music, and it’s brave. But this is also a country where you have media competition and sometimes it’s out of control.”

For Wenger the nadir occurred when Annie’s 12-year-old son was hounded by tabloid reporters. “That was not very fair, no,” he says quietly.

He held an impromptu press conference outside Highbury and the way he spoke was so convincing that the lies suddenly stopped. “But it left something in crowds that were vicious,” he recalls. Years later vitriolic supporters still resorted to chants calling him a paedophile.

Wenger “knitted myself a soul in red and white” as he showed an unbreakable loyalty to Arsenal. But, as happens so often with great managers, he lingers over the defeats. As a young manager at Nancy, Wenger was stricken by a loss just before the Christmas break. He was so desolate – “like a zombie” – he spent Christmas and the next three weeks alone.

He believes “that dark place” was “where I learnt patience, endurance and rigour”. “I had problems in coping with defeat. I did throw up sometimes and it took me time to recover from a defeat. I wondered if I am made for this job because when you suffer so much physically you will not survive. But I had always a quick recovery. I am an optimist, basically. I thought: ‘Let’s go to the next one.’”

Was he ever physically sick after an Arsenal defeat? “I was more mentally sick. I made 1,235 games for Arsenal and didn’t miss one. I can’t remember when I stayed in bed to miss training in 22 years. But, after defeat, you never sleep. You have an internal film that goes through your mind. It’s a sense of anger, humiliation, hate. The next day you have to put that into perspective but every defeat is still a scar on my heart.”

In 2003-04, when his Invincibles did not lose a league match the whole season, he had “no fear of anything. Just go to a game and play – and you will win. I wanted to play the perfect season. Usually when you win the Premiership, two or three games later you suffer a loss. I told the players: ‘You can become immortal if you continue to focus.’ That’s what happened.”

The inevitable end to the record unbeaten run came in the fateful 50th match, in a controversial defeat against Manchester United at Old Trafford. “You felt a sense of injustice because we did not deserve to lose this game,” Wenger says. “Rooney got a soft penalty and, in the first 20 minutes, Ljungberg was clear through and Rio Ferdinand should have been sent off. With VAR today he would have gone. What was bad is we climbed Everest and fell to earth again. Now you tell the players we have to climb up again. That’s difficult.”

Wenger was haunted most by the Champions League – and especially the 2006 final when, reduced early on to 10 men, they led 1-0 until the 79th minute when they conceded two late goals to Barcelona. “We had beaten Real Madrid with Ronaldo, Figo, Zidane and Raúl and we did not concede a goal in the whole knockout stage. We beat Juventus who had Vieira, Ibrahimovic, Trezeguet. It was hugely frustrating. We twice had chances to score the second goal and if we’d played with 11 against 11, we would definitely have won the European Cup.”

More happily, he has not forgotten the sweetest victories. “With a young team we won against Madrid with a fantastic goal from Thierry Henry, and when we won in Milan they were European champions. Their crowd stood up and applauded us. Those are moments where you play the game like you want it to be played – as when we won 5-1 at Inter [in 2003]. But you remember the defeats more.”

..